Recently I had the opportunity to work in a small seminar group on the design of change processes in complex systems. Organization developers from all parts of the USA met in Leesburg, Virginia, about 40 miles from Washington D.C. Although I was the only European, the degree of cultural diversity was high: the countries of birth of the eight participants included India, Peru, Libya, the USA and, in my case, Austria. Skin color, age, professional background - we couldn't have been more different.

Over the course of the seminar, this diversity reflected exactly what is required when dealing with complex systems: the more varied the perspectives from which we view complex situations, the better.

Just as Marcel Proust put it:

"The voyage of true discovery lies not in seeking new landscapes, but in seeing with new eyes."

When is a situation complex?

Religious historian, James Carse, provides a philosophical explanation which is also pertinent for the economy. In his book, "Finite and Infinite Games", he distinguishes between (life) games that have a clear end and those that are practically infinite. Football, chess, perhaps parenthood, in earlier times education, these are all games that not only have a beginning and end, they also have clear rules. If we break them and get caught, we have to bear the consequences. So, we set ourselves clear and SMART goals, make strategies, create plans and milestones. In a finite game, we know what we have to do if we want to succeed. If we don't succeed, we think we've done something wrong.

At the same time, we know intuitively that this game often works differently in real life. Our holiday plans are thwarted by bad weather that we cannot control, our business strategies derailed by (br)exits or politicians who want to make their countries "great again". Of course, there are still rules in an infinite game, but they can change quickly and without much notice: market conditions, legal framework conditions, stock market prices, environmental events.

We live in a world marked by the acronym VUCA: volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous. In this VUCA world, we can still be goal-oriented, but at the same time we must understand that our efforts can be in vain due to unforeseeable circumstances. We have to learn to adapt.

Wicked problems

For all these reasons, we are seeing a marked increase in the number of so-called wicked or sticky problems in organizations. These are the problems that remain despite many attempts to find solutions. They cannot be eliminated by linear, tried and tested attempts at solutions or changes.

So, when is a situation complex? In an organization, a situation is always complex when the measures taken to solve the problem so far have been unsuccessful.

As it makes sense to distinguish between finite and infinite games in life, in organization development we should also differentiate according to the degree of complexity of the situation we want to change.

If things work, complexity thinking is not required. Nor do we have to follow the principles of complexity thinking if we can identify clear causes of problems and use proven methods to solve them.

There are also situations in change management in which linear development takes place and change can be easily controlled. Precise guidelines or phase models, such as John Kotter’s well-known 8 steps of change, are helpful in such cases.

But if the results of our efforts slow, if we cannot identify the causes or if our efforts do not produce the desired results, then these are signals that a fundamentally different approach is required. Linear and phase-oriented change models must be replaced by other instruments.

Incidentally, attempts at change in complex problem situations automatically have an experimental character because the result is not clearly predictable. It is precisely in such an environment, however, that innovation and, often surprisingly, radical renewal emerge.

How do we design changes in complex systems?

We need tools and methods to deal with the emergence of uncertainty during change processes. These tools no longer automatically follow the classical principles of clearly formulated objectives, milestones and final evaluation of measures. From chaos research, we know that even slightly different repetitions of an experiment in long-term behavior can lead to very different results. Exact repetitions are impossible in social systems - and all companies are social systems. Therefore, we are often unable to fall back on proven models.

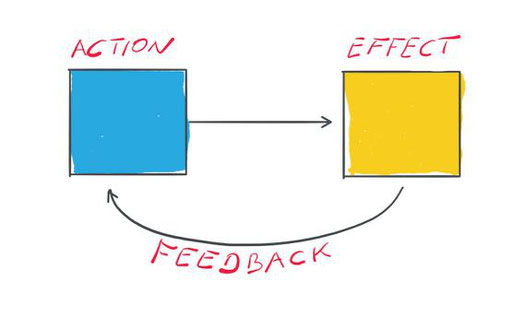

What can we do now to achieve the desired results in the long term? We can focus on the patterns and behaviors that we experience in our organization. Our actions are based on these observations. The results are fed into a permanent feedback loop. If necessary, we repeat this several times until we achieve appropriate results.

We support this process through adaptive action, whereby we deal with three questions:

- Which repetitive phenomena and behavior patterns can we observe?

- How do we interpret these phenomena?

- What is the next immediate action or intervention that we can meaningfully derive from it?

The concept of Adaptive Action introduced by Glenda Eoyang and Royce Holladay proves helpful here. The procedure consists of three steps.

1. Collect data

First of all, we need reliable data on the following questions:

- What phenomena do we perceive in our organization?

- Which behaviors do we perceive?

- Which ones occur more frequently?

- Can we recognize any patterns?

To avoid jumping to early conclusions, it can be helpful to record the observations with the help of the polarity model. For example, if we perceive a conflict between purchasing and production, we record the two positive polarities "cost-consciously - quality-consciously", so we can then continue to work constructively and in as positive a mindset as possible.

Techniques such as qualitative in-depth interviews, the “Trigon Aspect Grid” or similar instruments can be very helpful for this data collection.

2. Interpret the data

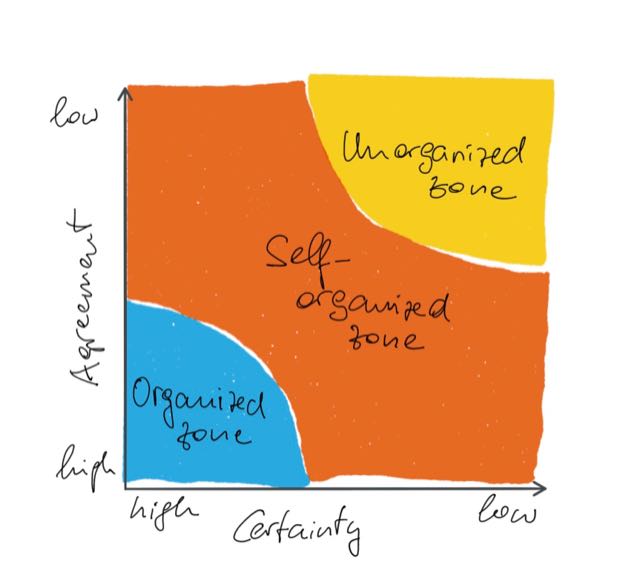

These data are then interpreted with regard to their significance and consequences. A helpful step here is to distinguish between organized, unorganized and self-organized zones within a company or department.

In every system there are things that work smoothly. We perceive these things as ordered. They are stable. This stability is influenced by two factors (see Eoyang and Holladay, 2013):

a) By the degree of agreement between people influencing a system pattern. Thus, most companies' employees may agree that customer orientation is an important company value, but there may be very different strategic ideas on how best to ensure it.

b) The degree of certainty that exists in the organization's environment about this system pattern. If employees do not receive their wages on time, they will quite certainly worry about the company's financial situation or become angry about the sloppiness. If, on the other hand, a company invests in a new technology, it is much more uncertain whether this investment will pay off.

No organization wants chaos in the area of payroll accounting. Team building activities, the introduction of regulations and working agreements can be methods that expand this order zone.

However, stability is not beneficial in every situation. Stable marketing processes easily overlook changes in the market environment. Innovation processes never emerge from stable conditions, but always require dynamism or even chaos. It is no coincidence that the Austrian-American economist Joseph Schumpeter speaks of the creative destruction that is necessary to produce innovation.

In the unorganized zone, these dynamics and tensions abound. This means, on the one hand, that this is fertile ground for the emergence of innovation, but, on the other hand, conflicts are frequent because things are perceived as chaotic. The point is not to wear oneself out. Chaos is hard to endure long term.

Between the organized and the unorganized zone lies self-organization. In this zone there is permanent movement, spontaneous cooperation in working groups that form quickly and dissolve just as quickly. There are surprises; solutions are emergent, but not repeatable.

3. Plan the next action

In the course of interpreting the data and perceived patterns, an organization development process in a complex environment will ask itself the following questions based on this landscape diagram:

- Where do we stand with our different tasks?

- Where do we want to go?

- How do we want to get there?

We derive the immediate next action or intervention that we can meaningfully take from the answers to these questions.

Stable states are resistant to change. Interventions that aim at change in the organized zone aim at creating tension and the resultant energy that enables change and dynamics.

The unorganized zone requires methods that form a container for the fears associated with uncertainty. Relationships must be consolidated. A mindset that strives for innovation must be created.

Further, self-organization does not organize itself. Like the other two zones, it needs containers that make it possible.

Our interventions will therefore answer the following questions:

- Which containers are necessary to maintain the desired states of organization, disorganization and self-organization? Such containers can be working groups, meetings, rules and regulations, communication systems and many more.

- Which differences must be brought about in order to enable a change from one state to another? Only the emergence of difference makes it possible to overcome the moment of inertia, bring about a change of pattern and arrive at new modes of behavior.

- And finally: what exchange is required between those involved in order to achieve the desired state? This exchange can be related to information exchange, resources, energies used or distribution of profits, etc.

Conclusion

In complex systems, we cannot predict with certainty which measures will have which effect. Organization development in a complex environment is an iterative process. The process provides us with feedback on the organized, self-organized and unorganized zones within the company. We can then take new actions based on this feedback and our ideas.

A comparison: when Apple or Microsoft introduce an update to their operating systems, it is not done with the aim of finding a final solution for the optimal operating system, but simply to generate innovations that benefit the customer. Similarly, in complex change issues we do not look for the final solution for the operating system of our organization, but work continuously on our company in an adaptive way. We do this as best we can but remain aware that the best possible outcome may never be achieved.

References

Carse, James (1986), Finite and Infinite Games. New York.

Eyang, Glenda H. und Royce J. Holladay (2013), Adaptive Action. Uncertainty in Your Organization. Stanford, CA.

Kotter, John (2012), Leading Change. Harvard Business Review Press.

LaCour, Deat (2019), Facilitating and Managing Change in Complex Systems. NTL National Training Laboratory workshop material. Unpublished.

Stacey, Ralph D. (1996), Complexity and Creativity in Organizations. San Francisco.